ROBOTICS

A question of trust: how the offshore industry is pioneering human-to-robot communication

Researchers at the ORCA Hub have developed MIRIAM, a new form of communication that allows users to ask robots questions and understand their actions in real time. Julian Turner talks to Helen Hastie, professor of computer science at Heriot-Watt University and an ORCA work package lead.

C

ommunication and trust are integral to the success of any collaborative project, and are two of the central themes of research being carried out by the ORCA Hub – a consortium led by the Edinburgh Centre for Robotics, a partnership between Heriot-Watt University and the University of Edinburgh, and joined by Imperial College London, Oxford University, and Liverpool University – into human-robot interaction.

Autonomous robots can sense their environment and make decisions by themselves, but, critically, they cannot explain why they choose a certain course of action; for example, changing course in order to recharge, or rising to the surface to reset the GPS. Because much of robot behaviour remains opaque to humans, operators might not have 100% confidence in their ability to carry out certain tasks in remote, hazardous environments involving multiple vehicles and platforms, such as those in the offshore industry.

“Robots have been working well in static modes in structured and predictable environments such as automotive manufacturing plants, but certain challenges remain over the widespread use of robotic and AI solutions in the offshore sector, primarily around adoption of this technology,” explains Helen Hastie, professor of computer science at Heriot-Watt University and an ORCA work package lead.

“This is particularly true where the robot is beyond the direct line of sight, where situational awareness might be low.”

Credit: ORCA Hub

Meet MIRIAM: a new way to communicate with robots

The ORCA scientists have developed a new method of communication that allows machines and humans to speak the same language and understand each other’s actions in real time. In doing so, they hope to build the confidence of those who will be using them and overcome adoption barriers in the workplace – leading to improved safety and efficiency and, ultimately, new ways of working.

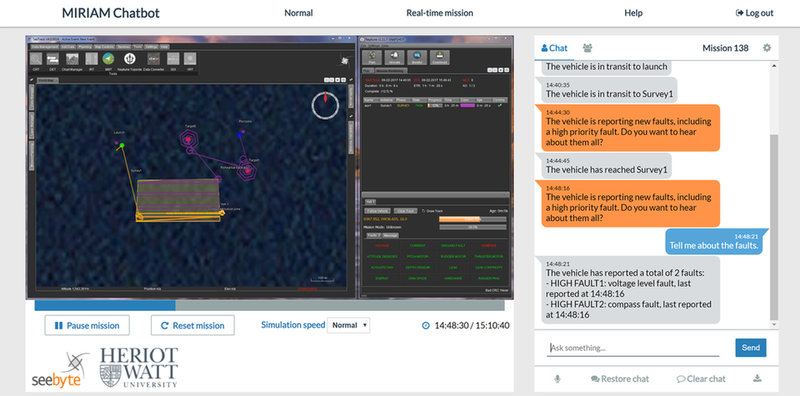

Multimodal Intelligent inteRactIon for Autonomous systeMs, or MIRIAM, allows energy, underwater, and onshore industry workers to ask robots questions, understand their actions, and receive mission status through a digital twin, the term used to describe a digital replica of an actual physical asset.

Because it is essential that a supervisor understands what the robot is doing and why, the scientists took a user-centred approach to the system’s design. MIRIAM uses natural language, allowing users to speak or text queries and receive clear explanations about a robot’s behaviour in an intuitive way.

MIRIAM allows natural language commands to be given to initiate robot movements

“MIRIAM allows natural language commands to be given to initiate robot movements, direct their activities and, for example, ask them to send back an inspection image from their location,” explains Hastie. “Using the latest state-of-the-art visual and natural language processing techniques, the goal is for MIRIAM to be a collaborative team member, working seamlessly with operators for joint decision making and increased situational awareness, and eradicating unnecessary aborts or laborious manual manipulation of the robot.”

When MIRIAM tells the user about an item of equipment, the name of that item is given meaning by its place and purpose on the platform. It is this context that forms the bridge between the user’s mental model and the system’s own internal representation of the world and a variety of key data.

“Such situated dialogue enables the system to determine what the user says by providing a structure that helps it identify specific named objects from the millions in its database,” says Hastie. “Once that object is identified, it provides further focused context around which the subsequent talk is framed.”

Common language: enabling a joint shared view of the world

Interestingly, Hastie and her colleagues discovered it was not just the robot giving an explanation that was important, but also how it was given, with different users requiring differing levels of detail.

“Expert operators prefer to know all the possible reasons but don’t necessarily need all the detail,” she explains. “If the explanation is longwinded, they can feel their time is being wasted. On the other hand, if an inexperienced operator hears a short – and for them, incomplete – explanation, they may feel the system lacks enough transparency for them to make an informed decision.

“The development of the MIRIAM dialogue system is informed by the way actual users want to talk to it,” she continues. “We worked with operators of real autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) and ground robots to find out their different styles and the phrasing they use. This has helped us to train our intelligent dialogue system so that it can understand what users ask in the context of the remote robot environments.”

The first MIRIAM prototype was trialled with real AUVs at Loch Linnhe on the west coast of Scotland, providing vehicle status and post-mission reports on subsea pipeline infrastructure, and successfully increasing situational awareness and trust, as well as facilitating training.

The development of the MIRIAM dialogue system is informed by the way actual users want to talk to it

In collaboration with French oil and gas multinational Total, the system has been further developed to enable operators to interact with surface vehicles on oil and gas platforms through a digital twin.

MIRIAM will allow humans to communicate with the digital twin via text or speech, meaning staff can ask where the robot is going, what it plans to do next and why, and query data it has gathered.

“Offshore energy platforms are complex environments packed with a myriad of different items of engineering equipment; for example, valves and gauges for controlling and monitoring fluid flows,” says Hastie. “An operator viewing an image of a scene on one of these installations needs to be able to accurately discuss and query the inspection system about individual pieces of equipment among many thousands of other items. MIRIAM enables this through a joint shared view of the world.”

Credit: ORCA Hub

Renewed optimism: MIRIAM’s real-world applications

MIRIAM will initially work with a tracked robot on routine inspections and preventative maintenance at Total’s Shetland Gas Plant, with the aim of removing personnel from the hazardous environments found offshore, reducing carbon footprint, providing valuable data, and reducing operational costs.

However, with an increasing number of oil and gas majors investing in the transition to renewables, the technology has obvious potential for other industries such as offshore wind, as Hastie explains.

This disruptive approach would ensure full situational awareness and allow for preventative maintenance

“MIRIAM would provide a valuable communication tool between human and autonomous systems for any beyond visual line of sight scenario, such as offshore turbine inspections using AUVs or airborne vehicles,” she says. “This disruptive approach would ensure full situational awareness and allow for preventative maintenance, enabling platforms to run efficiently, with reduced downtime.”

Communication and trust: the MIRIAM project accentuates both, and is a welcome opportunity to feel optimistic that human/machine collaboration may ultimately lead to a cleaner, safer world.