Operations

How a ‘smoke alarm for the sea’ could keep abandoned wells safe

Researchers are developing a new technique to monitor the long-term integrity of decommissioned or suspended oil and gas wells in the North Sea. The project aims to provide an early warning system for abandoned wells, potentially preventing dangerous leaks. Umar Ali found out more.

Credit: Henning Flusund

T

he North Sea is currently home to about 11,000 oil and gas platforms, of which 2,379 are expected to be decommissioned in the next ten years. However, the oil and gas industry lacks a standard approach to identifying environmental liability and well integrity.

There is currently no obligation for oil and gas companies to inspect abandoned wells, and although suspended wells do need to be inspected the process is not frequent or continuous.

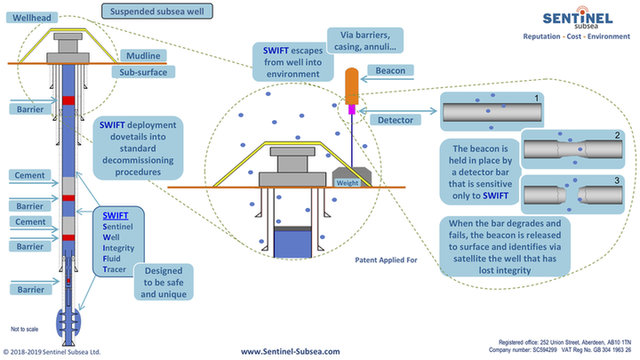

A collaboration between Heriot-Watt University, Aberdeen-based integrity specialist Sentinel Subsea and the UK Oil & Gas Innovation Centre aims to address the problem of monitoring unused wells with an “environmentally benign tracer compound.”

“During 2017, for the first time, the number of wells being decommissioned was higher than the number of new wells being drilled,” said Oil & Gas Innovation Centre CEO Ian Philips. “With the total decommissioning expenditure over the next ten years expected to reach £15.3bn on the UK continental shelf alone, collaborations like this have the potential to bring further cost efficiencies and increase environmental safety standards to the sector.

“The industry as a whole is striving to reduce decommissioning expenditure by 35% by 2035 and this non-invasive, environmentally-friendly monitoring system has the potential to monitor thousands of decommissioned and suspended wells across the UK and further afield at low cost.”

How does the compound work?

The compound, known as SWIFT, is designed to be pumped into a well before it is sealed and will react with a detector “trigger” material if the well leaks. Once this tracer-trigger reaction takes place it will cause a buoyant beacon to detach and transmit a signal to its base station, alerting the need for further investigation of the beacon’s associated well.

“Environmental assurance and cost reduction are the two cornerstones of well decommissioning,” Sentinel Subsea CEO Neil Gordon said. “It is vital that the North oil and gas industry can ably demonstrate proactive, best practice of environmental stewardship to all stakeholders throughout the late life and decommissioning process, whilst working towards the Oil and Gas Authority’s reduction target of 35% on current cost projections.

“Sentinel Subsea’s technology provides that environmental assurance whilst providing the confidence for industry to adopt innovative decommissioning techniques that could make a huge contribution to that cost-saving objective.

“Our partnership with Heriot-Watt University, supported by the Oil & Gas Innovation Centre, allows our technology to begin its tangible journey to make global decommissioning a safe, highly efficient industry.”

Infographic image courtesy of Sentinel

Development of the system

According to a statement from Heriot-Watt University, development of the SWIFT compound is showing “promising results” in the laboratory, but there are a number of challenges in developing a reliable early-warning system. For the compound to work as a “smoke alarm in the sea” false positives must be eliminated and the beacons must be able to detect the tracer-trigger reaction.

“The SWIFT compound we are developing cannot be found naturally in the environment as this could cause a false positive detection but must, at the same time, be completely non-toxic and non-hazardous to allow it to enter the sea environment from the well,” Heriot-Watt professor David Bucknall said. “We also need to ensure that it does not react with any of the materials and compounds that exist in the wells already.

“It also needs to remain ‘dormant’ for an extended period of time, sealed within the well. We are testing materials that can last for up to 100 years by artificially ageing the compound under lab conditions. The position of the trigger on the seabed means it can be more readily replaced so this will need to last for approximately ten years.”

The project is focusing on three stages to ensure the system is commercially viable. These stages include the chemical design, which is currently underway; simulated and laboratory field trials; and independent external validation tests.

Following these, the compounds will be commercially produced in sufficient quantities for Subsea Sentinel to conduct trials in North Sea wells before scientists at Heriot-Watt evaluate the trial data to ensure the system’s functionality matches results from laboratory trials.

Widespread production of the system is expected to start in spring/summer of 2019.

The licences cover a huge area in very deepwater, averaging 3,200m.

Ongoing Challenges

Despite all the promise, so far, not a single well has been drilled in the west and south west of Crete - so what is holding back serious activity?

Edgar van der Meer, senior analyst at NRG Expert, says investors may still be wary of the financial stability in the Greek economy, as well as the political risks, coupled with the unknown quantity and quality of potential resources, meaning investment in the area ‘is deemed risky.’

“Greece has had a very unstable political and economic climate, which has detracted and deterred foreign investment,” he says.

Another issue is a lack of momentum from the government, say Morris.

“When blocks are awarded they need to go through a ratification process to confirm the awards but that can take up to two years; it is not a fast process and there are many environmental and permitting considerations that add to the timeline,” he explains.

HHRM, the public authority in charge of hydrocarbons resources management, could use more support for staff and money too, says Andriosopoulos.

“Another important challenge is modernising the terms offered for future contracts to reflect the realities in the market; only then will investors be interested in hydrocarbon exploration and production in Greece,” he adds.

While the Greek government has acknowledged the importance of competitiveness and investment in its offshore energy sector, especially after the decade-long economic crisis, Andriosopoulos, says: “More political will is required to support the set goal of turning the country into an energy hub and realising the energy and climate goals for 2030.”

Competition from renewables is also heating up

Hydrocarbons also have competition in the region from renewables, for which Greece has great potential. The Greek energy and climate plan, published in 2018, emphasises the development of renewables and energy storage, the cost of which is dropping on an annual basis.

The Greek ministry of energy recently submitted its National Energy and Climate Plan, which outlines a transition to a green economy, in particular noting a radical change of Greece’s energy mix in favour of renewables for up to 32% of final consumption.

Despite all the promise, so far, not a single well has been drilled in the west and south west of Crete.

However, Andriosopoulos says even as the share of renewables continues to grow, fuels such as oil and gas will continue to take up a large percentage in the energy mix for many years to come and “cannot be abandoned.”

But he cautions: “If developments in hydrocarbon exploration is too slow, it may then be too late to use these fuels; there is a time frame of a couple of decades for these projects, since their profitability may come into question as time passes,” he notes.

Future outlook

Overall, should there be a significant find offshore Greece, “the region as a whole could stand to benefit significantly,” says van der Meer.

But considering the current rate of activity, and the potential technical challenges associated with deepwater drilling, the time frame for such a discovery is likely to still be several years away.

Commenting on recent new lease agreements, Greek Energy Minister George Stathakis has said he expects to see “the extent and size of [Greece’s] deposits in two to four years.”