Regulation

America’s offshore regulator: is it doing its job?

Following the Deepwater Horizon disaster, the US offshore industry has been under pressure to improve its performance. However, its regulatory body, the Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement, has drawn criticism for overly industry-friendly legislation and weak authority. JP Casey asks, is it fit for purpose?

Credit: Henning Flusund

T

he Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSEE) is responsible for regulating operations and ensuring safety in the US offshore industry, a vast operation for the body. A total of 41 offshore rigs were operational in the Gulf of Mexico in 2018 alone, and the region’s daily oil production peaked at 1.7 million barrels.

While the industry’s production figures have remained consistently strong, its safety performance has been significantly weaker. The 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill killed 11 people and leaked over three million barrels of oil before the damaged well was capped, serving as a stark reminder of the industry’s inherent dangers, and raising concerns about the US’s commitment to ensuring operational safety.

These concerns have been intensified by a Trump administration that has largely supported offshore expansion into waters that contain 89.9 billion barrels of untapped oil, according to the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM).

Expansion into these waters have been met with significant pushback, with environmental law firm Earthjustice taking the government to court for its attempts to roll back legislation introduced in the wake of the Deepwater Horizon disaster. Similarly, conservation group Oceana has published a report entitled Dirty Drilling, highlighting a number of the body’s actions that the environmental group claims undermine safety and weaken environmental regulations.

As industry and environmental groups fall into conflict, the BSEE has found itself stranded somewhere in the middle, having to balance industry interests on one side and environmental protection on the other, often supporting the offshore industry more readily than many conservation groups would like.

Industry influence over policy

“BSEE’s incorporation of industry-written standards into regulations does not ensure safety and allows the industry to govern itself without adequate independent oversight,” said Oceana campaign director Diane Hoskins, highlighting its concern that the body may be more interested in pacifying offshore companies than ensuring safe operations.

“Despite warnings, BSEE continues to rely heavily on safety standards written by the American Petroleum Institute for federal regulations,” she continued. “There’s a clear conflict of interest. BSEE is essentially relinquishing its independence, blurring the line between regulator and regulated.”

Oceana claims that this emphasis has helped push the US offshore fatality rate to seven times that of other US sectors, and four times higher than offshore sectors in Europe, with a fire or explosion taking place once every three days between 2007 and 2017, and 1,568 injuries reported between 2011 and 2017.

US offshore companies have daily operating costs of $1m, while the average fine levied at a company is just $44,675 per day per violation.

The group also criticised the BSEE’s lenience with regard to fines for projects that break its regulations, suggesting that both rules and punishments are too lax to be effective. The report notes that US offshore companies have daily operating costs of $1m, while the average fine levied at a company is just $44,675 per day per violation. This average amounts to just 0.8% of the $5.6bn in revenue reported by US offshore firm Baker Hughes in the first quarter of 2019 alone.

This combination of ineffective legislation and punishments helps maintain what Hoskins called a ‘vicious cycle’ with regards to safety performance. While the BSEE points to the National Technology Transfer and Advancement Act, which requires to incorporate industry standards into its own legislation, critics have claimed that the BSEE has relied too heavily on offshore companies, enabling them to influence policy matters beyond the scope of this bill.

“There are systemic problems across the board: industry continues to struggle to improve its safety culture and BSEE’s current inspection and enforcement actions do not result in comprehensive oversight of offshore drilling activities,” said Hoskins. “It’s a vicious cycle and too many American offshore workers are still dying or getting injured on the job.”

Regional competition is stiff

While there have been several notable gas discoveries in the East Med - including Tamar (7-10tcf) and Leviathan (18.9tcf) fields in Israel and the Aphrodite (~7tcf) and Calypso gas fields in Cyprus, as well as the more recent ones - as noted by Morris, many face challenges commercialising amid challenging access to the European gas market and geopolitical tensions.

Cyprus, for example, is currently considering export opportunities to Europe via a new LNG plant or a new gas pipeline - both of which will probably require more gas to be discovered to make the investment commercially viable.

Whereas gas found offshore Greece, which borders Albania and Bulgaria, has an easy overland route to the rest of the European market, where gas is a core part of the energy mix.

While natural gas demand in Europe is levelling off amid more renewable energy production, supply is also declining. The EU currently imports about 20% of its gas needs, mostly from Russia, and is keen to find new supplies.

“The addition of an entirely new productive gas region would be huge news for Europe,” says Professor Kostas Andriosopoulos, an academic director at ESCP Europe.

“If we take into account Greece's proximity to the Balkan markets, dominated by Russian oil and gas, new discoveries would also bear fruit when it comes to their energy independence.”

Furthermore, Greece itself would benefit through the reduction of gas imports from places like Russia and Algeria, while local consumers could enjoy lower prices, he adds.

Falling oil prices – over an extended period of time – and a rise in the demand for renewable sources will shape the industry of tomorrow.

While there have been several notable gas discoveries in the East Med - including Tamar (7-10tcf) and Leviathan (18.9tcf) fields in Israel and the Aphrodite (~7tcf) and Calypso gas fields in Cyprus, as well as the more recent ones - as noted by Morris, many face challenges commercialising amid challenging access to the European gas market and geopolitical tensions.

Cyprus, for example, is currently considering export opportunities to Europe via a new LNG plant or a new gas pipeline - both of which will probably require more gas to be discovered to make the investment commercially viable.

Whereas gas found offshore Greece, which borders Albania and Bulgaria, has an easy overland route to the rest of the European market, where gas is a core part of the energy mix.

While natural gas demand in Europe is levelling off amid more renewable energy production, supply is also declining. The EU currently imports about 20% of its gas needs, mostly from Russia, and is keen to find new supplies.

“The addition of an entirely new productive gas region would be huge news for Europe,” says Professor Kostas Andriosopoulos, an academic director at ESCP Europe.

“If we take into account Greece's proximity to the Balkan markets, dominated by Russian oil and gas, new discoveries would also bear fruit when it comes to their energy independence.”

Furthermore, Greece itself would benefit through the reduction of gas imports from places like Russia and Algeria, while local consumers could enjoy lower prices, he adds.

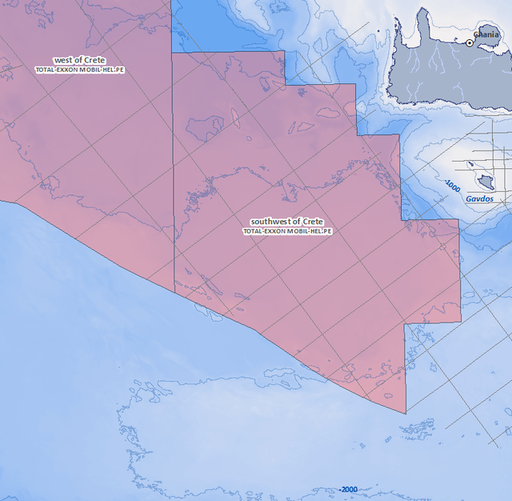

Credit: Courtesy of Hellenic Petroleum

Ongoing Challenges

Despite all the promise, so far, not a single well has been drilled in the west and south west of Crete - so what is holding back serious activity?

Edgar van der Meer, senior analyst at NRG Expert, says investors may still be wary of the financial stability in the Greek economy, as well as the political risks, coupled with the unknown quantity and quality of potential resources, meaning investment in the area ‘is deemed risky.’

“Greece has had a very unstable political and economic climate, which has detracted and deterred foreign investment,” he says.

Another issue is a lack of momentum from the government, say Morris.

“When blocks are awarded they need to go through a ratification process to confirm the awards but that can take up to two years; it is not a fast process and there are many environmental and permitting considerations that add to the timeline,” he explains.

HHRM, the public authority in charge of hydrocarbons resources management, could use more support for staff and money too, says Andriosopoulos.

“Another important challenge is modernising the terms offered for future contracts to reflect the realities in the market; only then will investors be interested in hydrocarbon exploration and production in Greece,” he adds.

While the Greek government has acknowledged the importance of competitiveness and investment in its offshore energy sector, especially after the decade-long economic crisis, Andriosopoulos, says: “More political will is required to support the set goal of turning the country into an energy hub and realising the energy and climate goals for 2030.”

Sanzillo urges oil and gas companies to begin thinking about their future investment in research and development and where that finance and expertise should go.

Part of that strategy is partnering with governments to prepare the economy for tomorrow.

“Norway is at least beginning to talk about it,” says Sanzillo. “In the US, when defence plants close, we mobilise the entire economy in order to make sure there is a smooth transition for workers and the communities where those closures are taking place – changes in the fossil fuel sector will be even bigger.”

Despite the need for a refocus Sanzillo speak of, he’s positive about the industry’s ability to change: “Amongst other things, large oil and gas companies are like universities. They are research universities that have great capacity to do great things, they already have. They have the capability and have been a major driver of the world for decades. You hope they can do that again, just without destroying the planet.”

Government support for expanded drilling

The BSEE’s work, however, is made more difficult by US Government policy, which has recently promoted the expansion of offshore drilling despite environmental concerns. Prior to 8 June 2010, the BOEM reports that there were just 11 exploration plans submitted for new wells in the Gulf of Mexico, but this figure has leaped to 368 new plans since this date. The fact that 350 of these new plans have been approved and passed on to the next stages of permitting suggests that over the last decade, the government has encouraged more companies to make exploration applications, and directly enabled more of these applications to advance.

While the government’s attempts to open up more US waters to drilling was stalled by local opposition and legal troubles, including an Alaskan court blocking the opening up of Arctic waters to drilling, the conflict has left the BSEE in an awkward position. The body claims to work “to promote safety, protect the environment, and conserve resources offshore through vigorous regulatory oversight and enforcement,” but these goals are increasingly at odds with US government policy.

“It’s a bleak reality,” said Hoskins. “BSEE is failing to meet its responsibility to ensure that oil and gas exploration and development activities are conducted in the safest manner possible. Instead of following its mission, the Bureau is clearly focused on short-term cost savings to industry.”

Government influence is particularly concerning with regards to the Well Control Rule, a series of standards introduced by the BSEE in 2016 to regulate the construction of drilling wells, following the Deepwater Horizon disaster. The offshore industry has opposed the new restrictions, claiming they have made a number of installations obsolete without improving safety performance, and the Trump administration has tried to roll back this law.

The body claims to work “to promote safety, protect the environment, and conserve resources offshore through vigorous regulatory oversight and enforcement,” but these goals are increasingly at odds with US government policy.

The Earthjustice lawsuit against the administration, which represents ten environmental groups that claim the rollback will undermine safety standards and eliminate the current system of safety inspections, is a direct response to the increased influence of the administration over offshore policy, which is perceived to be damaging.

“BSEE seems intent on heading back to the pre-Deepwater Horizon days of safety oversight,” said Earthjustice associate attorney Chris Eaton. “Between issuing thousands of waivers of regulations, and rolling back the rules put in place to prevent another catastrophic oil spill, the agency is showing it’s not committed to working hard to ensure environmental protection and safety.”

Direct government influence has led to at least one positive environmental development, after then-interior secretary Ryan Zinke declared Florida exempt from new offshore operations in January 2018 after pressure from local opposition, led by then-governor Rick Scott.

However, the ruling prompted a surge of opposition from other coastal states opposed to expanded drilling, with the New York Timesreporting that 14 coastal governors were opposed to new drilling projects in January 2018, compared to six who were in favour, highlighting the inconsistent and at times random approach to offshore regulation in the US, which has raised questions about the influence of the BSEE.

Reforms and the future

The BSEE is not oblivious to these criticisms, and has committed to a number of initiatives in recent years to improve operational performance. The body received over $200.5m in funding for the 2020 financial year, a slight increase on the $199.9m it received for the previous 12 months, and announced the results of its first Risk-Based Inspection Program, which used data analysis and risk modeling to provide the equivalent of an addition 250 hours of risk assessment.

However, with the government and industry directing several aspects of the BSEE, questions remain about the body’s influence, and whether it will be able to direct policy in the future. Hoskins, for one, highlighted a shift towards popular opinion, and often public outcry, as the key drivers of change in the sector.

“While the offshore drilling industry is resistant to change, we know that public pressure can have a real impact on the direction of offshore development,” said Hoskins. “That public opposition only continues to grow today. Opposition and concern over expanded offshore drilling activities nationwide comes from every East and West Coast governor, more than 360 municipalities, over 2,200 elected officials from both parties, and alliances representing over 47,000 businesses and 500,000 fishing families.”

With the government and industry directing several aspects of the BSEE, questions remain about the body’s influence, and whether it will be able to direct policy in the future.

There are reasons to be optimistic for the US’s offshore energy future, however. Offshore renewable energy has significant potential, with the American Wind Energy Association reporting that offshore wind alone could produce up to 86GW by 2050, a significant expansion from the 2018 capacity of 25,434MW. Hoskins is hopeful that wind will be a key energy source as the US moves away from less sustainable forms of power generation.

“We should focus on transitioning towards responsibly sited renewable energy – like offshore wind – to supply the nation’s growing energy needs because the risks offshore drilling poses to coastal communities and marine ecosystems in the United States are too great,” said Hoskins.

“Coastal communities and our environment cannot afford another environmental catastrophe, which is where we are headed under President Trump’s proposals. It’s time for President Trump to stand with coastal communities, not the oil and gas industry.”

Future outlook

Overall, should there be a significant find offshore Greece, “the region as a whole could stand to benefit significantly,” says van der Meer.

But considering the current rate of activity, and the potential technical challenges associated with deepwater drilling, the time frame for such a discovery is likely to still be several years away.

Commenting on recent new lease agreements, Greek Energy Minister George Stathakis has said he expects to see “the extent and size of [Greece’s] deposits in two to four years.”