financials

The inevitable end of the oil and gas dividend?

“Dividends are considered pretty sacrosanct”, analyst Arindam Das tells us, but nothing is sacred in a pandemic. Matt Farmer asks: with much larger disruption on the horizon, will the largest oil and gas companies treat dividends the same way in future?

The year is 2020, and oilfields are leaking money. Oil and gas production companies take drastic action to preserve their finances, terminating staff contracts and minimising capital spending. These measures even included previously unimaginable changes to the millions flowing toward shareholders every quarter.

Which means that in 2020, big oil dividends did not rise quite as fast as investors would have hoped. Every year, medium and large oil companies pay billions to shareholders in order to keep investors interested in their business. These payments have become a core part of generating value, and board members have proved very reluctant to change this. Decreasing dividends is rarely in the interests of the company, or the personal finances of the board.

One of the clearest examples of the oil and gas dividend’s importance comes from US shale producer Chesapeake Energy. In February 2021, Chesapeake emerged from Chapter 11 bankruptcy restructuring after hitting hard times in 2020. By May, the company had announced payouts for its shareholders, in a move that would seem impossible in any other industry.

The pandemic marked a hard time for oil and gas, but plenty more awaits. As the energy transition progresses, the cost of decarbonisation will keep coming. Meanwhile, investors now look more toward ESG factors and greener companies. So how will investors and boards change their attitude toward dividends?

What happened to oil and gas dividends in 2020?

With the shock of Covid’s arrival in the rearview, the depth of the industry’s fever in 2020 has become clear. An intensive course of cost cutting was the most popular medicine at the time. For some, this included shareholder dividends, though the industry’s reluctance to alter payments remains clear.

ExxonMobil maintained its dividend, while making the first quarterly loss since Exxon and Mobil merged. Chevron increased its payments slightly, while others such as Total merely paused their dividends' previously unstoppable rise.

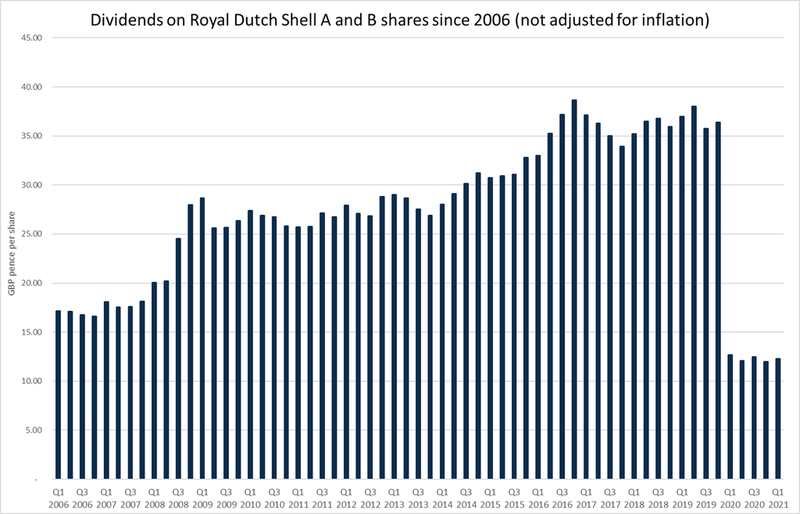

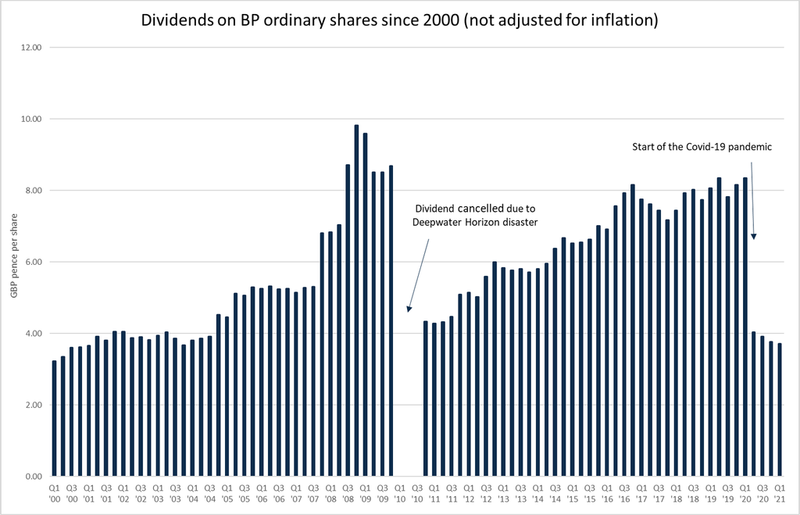

But for some, financial flexibility came first in the pandemic. BP and Shell halved their payments in the first quarter of 2020, while Equinor made even greater cuts. While such cuts would previously have scared investors away, these moves made sense to shareholders in a pandemic.

Arindam Das, head of consulting in EMEA for business analysts Westwood Energy, told us: “You would have to see a black swan event, like the pandemic, for companies to temporarily reassess their dividend policies and their strategies. When companies get to a point where they plan for $60 [per barrel], but the realised prices are at $40, that’s the point when they start to think about reassessing.

“Is that cutting your capital guidance? Is that delaying capital or delaying a project? Dividends are considered pretty sacrosanct for companies to remain a reputable investment proposition.”

You would have to see a black swan event, like the pandemic, for companies to temporarily reassess their dividend policies.

All of these changes gave companies some financial flexibility at the pandemic’s peak, and then allowed them to invest. Equinor, Shell, and BP all made significant moves toward renewable generation over the past year, in line with their stated company goals.

Business as usual has only recently resumed, with Shell spending at least 20% of its cash flow on dividends in the second quarter of 2021. Analysts expected this increase later in the year, but the rapid rising of oil prices helped the company’s finances.

While keeping dividends low, Shell managed to pay down billions of dollars in debts. Generally, the companies that survived the worst of Covid-19 look healthier for having done so. Now, the next big challenge has already arrived.

The expectation of dividends, and creating value in oil and gas

While company financials fluctuate, the energy transition continues. The largest companies continue to diversify and refocus away from oil and gas. BP and Shell have bought into wind projects. TotalEnergies rebranded and announced investments in car charging points and low-carbon fuels.

International supermajors receive the most scrutiny for their energy transition efforts and must cover the most distance to decarbonise. At the same time, these companies are deepest in ‘dividend culture’, and feel a certain weight of expectation.

Either you’re a dividend payer, or you come across as a growth-focused company that may be bought out.

Das says: “For upstream oil and gas companies, the primary mode of raising capital has always been from equity markets. When you go there, you realise that you’ve got to have some sort of investment proposition. Either you’re a dividend payer, or you come across as a growth-focused company that may be bought out, giving investors a premium.”

The expectation to produce dividends does not fall to all sections of the market, with nationally-owned companies having wildly different approaches. Analysis by Westwood Energy showed that Petrobras paid out approximately 5% of its operating cash flow to shareholders in the first three quarters of 2020. Meanwhile, Saudi Aramco paid out almost all of its cash flow to shareholders.

“People will need some way to give their shareholders returns”

Across the Atlantic, oilfields may head in the direction of the supermajors. Das says: “Investors want US shale companies to be much more profitable, not focusing so much around growth.

“Investors will want those companies to give them a certain degree of confidence in their ability to improve shareholder returns. I wouldn't be surprised if, as companies start to get much more profitable, they start dividends they may not have had previously, to remain [as good] investment propositions.”

Investors will want those companies to give them a certain degree of confidence in their ability to improve shareholder returns.

“European companies have long cycle, riskier offshore investments. They may choose not to pursue a very strong dividend policy, because they'll still want to maintain some flexibility in terms of their balance sheet cash conversion. As companies go through the transition and start to evolve, dividend policies may also evolve.

“Looking into a crystal ball, I think it's very hard to say people will do this or that. What we know for certain is that people will need some proposition to give their shareholders some returns, whether that's dividends, or share buybacks, or some other method.”

The energy transition’s impact on the value chain

The energy transition has made strategic changes and greater costs necessary at one end of the value chain. These changes affect investors at the other end, though not as much as the changing culture around investments as a whole. Some sources loudly claim “oil investments are drying up”, while many others have noted the rise of ESG investments and their better-than-average returns.

Investors increasingly choose to put money into ESG funds, which increasingly exclude oil and gas. Das believes this forms part of a temporary moment of flux for industry investments.

“There is a lot of concern around the industry, as investment managers become more aligned with net-zero goals. In tandem with the volatility driven by the pandemic, it's a perfect storm.”

How much investment returns to the industry depends to a large extent on how companies evolve their net-zero strategies.

“You're not sure what's going to happen in the near term, and you don't know what's going to happen in terms of climate strategies. That perfect mix has given investors a reason to pause and reassess their attitude towards the industry.

“How much investment returns to the industry depends to a large extent on how companies evolve their net-zero strategies, on how regulatory bodies pursue net-zero, and how investors feel about these factors.

“If you manage large sums of capital, you want to generate the returns that you have been tasked with. In the next three to five years, we probably won't see capital completely dry up for the industry, and we probably won't see all capital return to the industry, but it’s difficult to tell.”

Will oil and gas companies even want to maintain dividends in future?

Dividends have become so core to the finances of supermajor companies, the big picture of creating value in oil and gas can become obscured. In other industries, dividends form a much smaller part of generating company value. For example, renewable generation companies have smaller returns but attract investments with their potential for growth and technological advancements.

Asked whether oil and gas dividend culture will change, Das says he believes this is the wrong question: “Companies are assessing where they are in their evolution. As a function of that, they're assessing what the right mechanism to create shareholder value is. Dividends is one lever, and that could be the lever that they choose to continue using.”

We need to be patient with the industry to see how it evolves, and how it evolves as an investment proposition as well.

“Or they could choose to do something different, like focus a lot more on share buybacks to create value further down the line. I think for all European and US majors, across the board, the one thing that's true is that they still want to remain attractive investment propositions.

“We need to be patient with the industry to see how it evolves, and how it evolves as an investment proposition as well. It's very easy to take a polarised opinion about what should happen.

"We shouldn’t speculate about the future at this stage, because everyone's going through this transition together. We should be in a position where we need to be able to ask investors: as we transition, how should we think about returns? What are your expectations?”

US and the Gulf of Mexico

The number of active drilling rigs in the lower 48 states of the US, excluding the Gulf of Mexico, stood at 753 in February. This fell to 738 in March, before reaching a four-year low of 572 in April, the lowest since May 2016. As of 8 May 2020, the Lower 48 land rig count reached 355 rigs, according to Baker Hughes’ data.

When it comes to the sought-after oil and gas fields in the Gulf of Mexico, production is estimated to remain relatively flat. The US Energy Information Administration (EIA) forecasts an average of 1.9 million bpd over 2020 and 2021, almost unchanged from its 2019 average.

The administration said that it does not expect any cancellations to Gulf of Mexico projects announced in 2020 and 2021.

Before the oil price crisis in the first half of 2020, Shell had awarded a contract to Sembcorp Marine for construction of the topsides and hull of a floating production unit for the Whale exploration project in the US Gulf of Mexico. Later this year, uncertain economic conditions forced Shell to postpone the project to 2021.

Regarding crude oil production in Alaska, the EIA predicted that it would remain relatively stable, at an average of 460,000 b/d in 2020, and that it will slightly rise in 2021.

Norway

Oil companies operating in Norway, Western Europe’s largest petroleum producer, drilled just 30 exploration wells off the coast of Norway by the end of 2020. This marked the lowest level in 14 years, as announced by the Norwegian Petroleum Directorate (NPD) in October.

The search for new oil and gas reserves has also decreased from 57 drilled wells in 2019 and falls behind previous projections of about 50 wells.

The NPD said in a statement: "The decline in demand for oil and lower prices have led oil companies to reduce their exploration budgets for the year and postpone a number of exploration wells.”

Companies including Equinor, Aker BP, and Lundin Energy announced considerable cost cuts in the early phases of the Covid-19 crisis, attempting to preserve capital and weather the storm.

In response, NPD director of exploration Torgeir Stordal expressed concerns over the near future of the industry: "Without new discoveries, oil and gas production could decline rapidly after 2030."

In the meantime, Norway still believes that there are significant resources to be found beneath its seabed, which are projected at around 3.9 billion cubic meters (bcm), a slight decrease from 4 bcm two years ago, the NPD said.

Brazil

The Brazilian oil and gas industry has been deeply influenced by the unusual events of 2020.

In November 2019, Petrobras announced its 2020–24 investment plan, with a new budget of approximately $75.7bn (84.94% allocated to exploration and production). Despite the challenges, the company has not reported massive obstacles.

It also continued with its divestment programme of some upstream, midstream, and downstream assets, opening new opportunities for foreign investment.

During the Covid-19 outbreak, Petrobras and other oil companies shifted focus from their own projects onto divesting in ancillary projects, which helped reduce their expenses while generating income for the sale of such non-core assets.

November’s bidding rounds by the National Agency of Petroleum, Natural Gas and Biofuels (ANP), showed that the usual interest in Brazil’s offshore upstream rounds has plunged, which led to the suspension of the Brazil Round 17 for exploratory blocks under the concession regime.

Despite the hardships, the ANP managed to keep the First Cycle of the permanent offer, which involves a continuous offer of fields returned and exploratory blocks offered in previous tenders that were not acquired or returned to the agency.

The UK Continental Shelf

British consultancy Westwood Global estimated in September 2020 that the UK Continental Shelf (UKCS) was on course to reach a record low of offshore exploration wells this year, its lowest since companies started exploring the North Sea for oil in the 1960s.

In May 2020, along with the publication of its annual review of global exploration activity and outlook for 2020 and beyond, the consultancy said that while dealing with the immediate Covid-19 crisis, “societal pressure is building for a rapid transition to a low-carbon future”.

In September, Alyson Harding, technical manager at Westwood, said in Energy Voice that the company predicts only five exploration wells will be drilled in 2020, one less than in 2018. By comparison, 14 exploration wells were drilled last year with only one becoming commercial.

According to Westwood’s early estimations from February, the UKCS was predicted to reach 17 wells by the end of the year, but the pandemic hampered these plans. So far, Chrysaor’s and Apache’s Solar well and Total’s Isabella well are commercially viable.

While the Oil and Gas Authority offered 113 licence areas over 259 blocks or part-blocks to 65 companies in early September, it is not certain that operations will take advantage of this opportunity because of current market instability.

Looking ahead, Harding said in a company webinar that the firm has been given indications from companies that 23 exploration and 10 appraisals wells could be drilled in the UKCS next year, depending on the impact of Covid-19 in 2021.

Mozambique

Mozambique’s untapped oil and gas potential was first revealed by initial exploratory drilling in 2007.

Later, natural gas became part of Mozambique’s oil and gas strategy to help industrialise the northern provinces of the country. However, after some recent project cancellations, Mozambique’s Council of Ministers is now planning to transport the north’s oil and gas to the better developed south.

In a tender process run in 2017, Shell was given the right to build a gas-to-liquids plant that would convert gas to synthetic diesel, naphtha, and kerosene; Norwegian chemical company Yara International was allowed to build a fertiliser plant to power the northern town of Palma using domestic market gas; and Kenyan power company Great Lakes Africa Energy was allocated gas to build a 250MW power plant in the north-eastern city of Nacala.

However, whether influenced by the Covid-19 crisis or rising environmental scrutiny in the country, it appears that only the Nacala power plant will take place. Yara has cancelled its fertiliser project and Shell’s CEO has been giving indications that the company does not expect to develop any new greenfield gas-to-liquids projects.