Interview

How will MethaneSat help to reduce methane emissions?

Following the launch of MethaneSat, the EDF's Mark Brownstein tells Eve Thomas about the satellite's potential for tackling methane emissions.

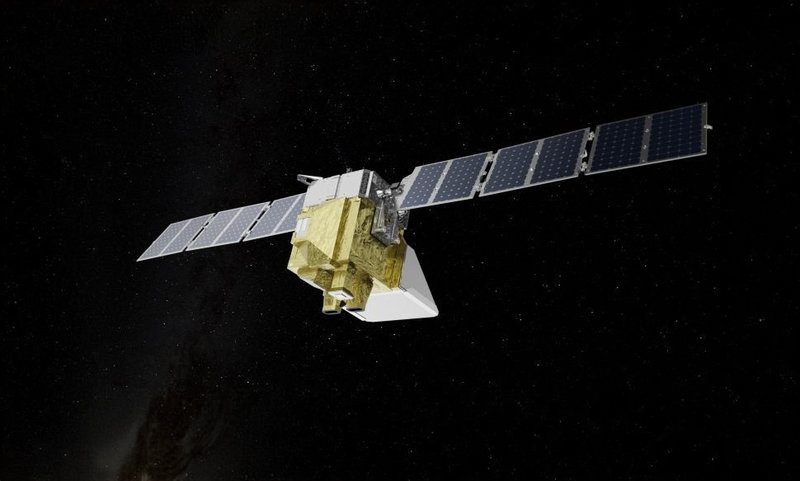

MethaneSat will provide data on global methane emissions. Credit: MethaneSAT

Arecently launched satellite known as MethaneSat is being touted as an essential tool in the reduction of methane emissions from the global oil and gas industry.

The first satellite developed by an environmental non-profit, namely the Environmental Defense Fund, MethaneSat will monitor methane emissions across the globe and transmit its data to radio relay stations worldwide.

It will particularly focus on methane emissions from the oil and gas industry, the second largest source of methane after agriculture.

Mark Brownstein, senior vice president for energy transition at the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF) environmental advocacy group, spoke to us about the potential of the technology to facilitate change in the oil and gas sector.

Eve Thomas: What does MethaneSat do, and how will it spot methane leaks?

Mark Brownstein: MethaneSat is a tool that's designed to provide us with comprehensive information on total methane emissions coming from the oil and gas industry. It will have the capacity to do an ongoing assessment of more than 80% of all oil and gas operations worldwide.

Importantly, it will have a level of sensitivity that no other instrument currently has, so we will get more total data than we can currently get. We'll get it on an ongoing basis worldwide because the instrument circles the globe 15 times a day, so we will also have the ability to attribute emissions geographically.

We will be able to use this for attribution to calculate not just the total amount of emissions coming from any particular point, but also the rate of those emissions.

It's very much a game changer because it is so comprehensive, and it is an ongoing diagnostic and reporting tool.

Eve Thomas: How will MethaneSat's data bring about change in the oil and gas sector?

Mark Brownstein: MethaneSat has been about six or seven years in development and, alongside the effort to design, build and launch the satellite, has been an equally committed effort to enact regulation and to secure company commitments.

We're now at a point where we have the United States, finalizing comprehensive oil and gas regulations that will be the most comprehensive and stringent in the world. We have the European Union, about to enact a set of regulations that will require not only reductions from domestic sources of emissions but also new reporting requirements for anyone selling gas into the into the Union, domestic or foreign.

We've got regulation in Canada, we've got regulation in Mexico, and MethaneSat is going to be helpful in the implementation of those regulations, holding both companies and governments accountable for performance under those regulations.

As well, at COP28, we had over 50 companies around the world commit to reductions in the next five years that should add up to about a 90% reduction in methane emissions from those that have made the commitment. We'll be able to use MethaneSat to assess how well those companies are doing in meeting the commitments that they made. Of course, we can also use MethaneSat to assess how companies who have yet to sign up for those commitments are doing as well.

It is an opportunity to be able to better assess the degree to which countries and companies are making progress and reducing emissions, and where there are opportunities to improve performance in the next few years.

Eve Thomas: Why have you chosen to focus first on oil and gas operations?

Mark Brownstein: Methane from human activity is responsible for close to a third of the warming that our planet is experiencing right now. There is nothing that we can do that will have a more immediate impact in slowing the rate of warming that's pressing down on all of us than reducing methane pollution.

The oil and gas industry is responsible for roughly a third of that pollution. Agriculture is also a source of emissions (largely cows and beef cattle), but also rice farming, and landfills are an important source.

However, the oil and gas industry, I think, is uniquely positioned to play a leading role. First of all, most of the oil and gas companies around the world are relatively well-capitalized and therefore have the resources to be able to tackle these emissions.

But also, methane is the key constituent in natural gas. Every molecule of methane that goes to waste in the atmosphere is one less molecule that can be put to use for energy and meeting the world's energy needs. At a time when so much of the world is scrambling to find new energy resource – either to replace that which we're no longer willing to buy from places like Russia, or, in the case of the Global South, where energy access and energy poverty is still an issue – methane abatement becomes low hanging fruit, not just to address the climate crisis, but also to address, global energy security needs.

Eve Thomas: Could MethaneSat act as a tool to bring about change in other industries too?

Mark Brownstein: MethaneSat will be able to see methane emissions from a wide variety of sources. The limitation, if there is any, is in how much data that we can download from the satellite in any given pass over radio relay stations around the globe. There's a certain amount of prioritization that we have to do just because there are limits to how much data we can import from the satellite on any given pass.

Additionally, it's not just about the data that the satellite is collecting, it's also about the algorithms that you develop to properly interpret and attribute that data. We have done the hard work of building that for the oil and gas industry.

One of our partners in this project is New Zealand, which is devoting resources to developing tools to be able to take MethaneSat data and use it for assessing agricultural emissions since that's a big priority of New Zealand's.

Eve Thomas: How has methane pollution been identified and quantified until now?

Mark Brownstein: Up until this point, we've been collectively relying on data that is being reported by companies, to countries.

Our decision to pursue a methane satellite was built on almost a decade's worth of experience that we had doing field studies in the United States, Canada, Mexico, Europe, Australia and elsewhere using terrestrial-based technologies, aeroplanes, drones, handheld devices or devices posted at the fence line of facilities, so we've used a wide variety of tools.

What we know from all of those field studies that we've done is that there's no substitute for measured emissions. Companies historically have reported their emissions on the basis of engineering calculations, and – at least in the United States – we've shown that those engineering calculations serve to underreport emissions by 60%.

We expect that as we begin to gather data from MethaneSat, what we currently understand about the total magnitude of the challenge (and what we currently understand about who is a larger emitter) may change as we get more accurate information collected from real-time assessment.

Eve Thomas: Is MethaneSat a long-term solution?

Mark Brownstein: The satellite has a design life of at least five years, but with the equipment in space, design life is a conservative estimate of how long a facility how long a probe can last. Of course, there is the example of the Voyager probe, which had a very short mission, and yet continues to produce information 40 years after launch.

There really is no telling how long the satellite will be able to produce data, but it's at least fit for purpose through the 2030 timeframe, and likely years to come after that.

Eve Thomas: Will MethaneSat 'name and shame' the biggest polluters in oil and gas?

Mark Brownstein: There's no question that, with this tool, we're going to be able to better understand where the problems are and where the opportunities are to make reductions, but when I talk about accountability, I often remind folks that the student that goes to class does all the readings doesn't fear a final exam.

We look at MethaneSat as an opportunity for the good students in the industry to gain validation for the work that they've been doing, while using the information from MethaneSat to prod those that would linger in the bar to get back to work.