Feature

Explaining the UK’s energy mix under the Labour government

With increasingly ambitious renewable targets, all eyes are on Keir Starmer’s new government to see how the UK will pivot away from oil and gas. By Scarlett Evans.

Credit: Christopher Furlong Staff / Getty images

The Labour government is almost six months into its first administrative term in 14 years, and has already doubled down on its clean energy commitments: closing the UK’s last coal power plant in September, promising a halt of new North Sea drilling licences and increasing windfall tax on offshore operators as it targets a goal of net zero by 2050.

Yet the plan has received criticism from various quarters, with some saying progress towards renewable integration has been too slow, while offshore unions have sounded the alarm over workers being left jobless by a rushed transition.

With electrification on the rise across industries, (the government estimates a 40-60% rise in demand for electricity by 2035) the need to adapt the UK’s energy mix is becoming increasingly pressing, and though exact next steps remain uncertain, the general consensus is that rapid action is needed if climate commitment deadlines are to be met.

The UK’s current energy mix

As it stands, oil and gas remain significant sources of energy in the UK. Figures from the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero (DESNZ) show that in 2022 (the most recent full year with available data), 78% of the nation’s primary consumed energy came from fossil fuels – with 39% and 36% of this coming from gas and oil, respectively.

“As of the start of 2024, 83% of total domestic energy production and imports were fossil fuels,” said Paul Hasselbrinck, senior energy analyst at GlobalData.

“Moreover, 50% was oil, used in transport, in refineries and (re)exported; 31.5% was gas, of which less than a third of primary demand goes through power generation, with the rest going to households for heating, industrial use and other final consumers,” he added.

But there has been significant progress towards using large amounts of renewable power, with the DESNZ report finding around one-fifth (20.7%) of the UK’s primary energy consumption was from “low-carbon” sources in 2022, substantially up from 12% in 2012.

The UK, along with many other developed nations, is hoping for an energy mix that includes a gradually increasing amount of wind and solar power production, a slow reduction in oil and gas usage, with natural gas and nuclear power plugging the gaps when clean or low-carbon power sources suffer intermittency issues.

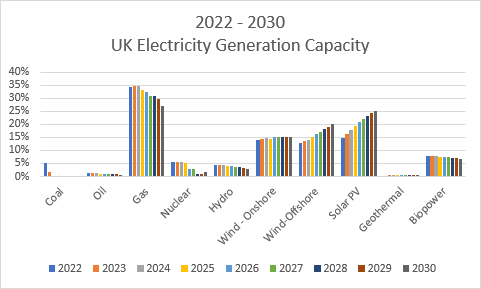

Source: GlobalData

“As gas comes off the system, we need to look at different ways of balancing it,” said Naomi Baker, senior policy manager at energy trade association Energy UK. “Key ways of doing this will be flexible demand and increasing battery storage.

“The former means adapting charging times during cheaper hours – for example a lot of EV charging can be done overnight during a time of reduced demand. This is still in its early stages, but in the meantime, battery storage is able to step in and do a lot of the heavy lifting.”

Barriers to battery rollout have dropped significantly in recent years, with costs declining 90% over the past ten years, and demand rising from 1GW to 4GW in the last four years. However, Baker said this still needs to increase by four to five times by 2030. This paints a picture of a nation with great potential for renewable power, yet with a long road ahead.

“The current targets for renewables in power generation are ambitious,” said Hasselbrinck. “Though the expected increase in the share of solar and wind are promising, if we look at the energy consumption from the whole economy and its sources, the transition seems a lot further away.”

This roadmap is made even more ambitious by Prime Minister Keir Starmer’s announcement at COP29 that the UK has a new aim of slashing its emissions by 81% by 2035, up from the 78% pledged by the previous Conservative government.

A wind down of oil and gas offshore projects is a cornerstone of Labour’s pursuit of these clean targets, imposing a halt on all new oil and gas exploration licences and increasing the windfall tax on North Sea operators from 35% from 38%. However, the moves have received criticism from both sides, targeted by some as too lenient, and by others as leaving offshore workers in the lurch.

The future of oil and gas

Even with Labour’s offshore clampdown, there are still numerous projects underway, with the North Sea Transition Authority estimating current projects could allow a potential 545 million barrels of oil equivalent to be developed in the North Sea by 2050.

Yet despite assurances that these projects will not be impacted by new government policies, the sudden turnaround could still create instability. The UK’s biggest union, Unite, has been particularly vocal about the potential dangers of banning new oil and gas projects – citing possible job losses and warning against offshore workers becoming the ‘coal miners of net zero’.

The group’s campaign, ‘No Ban Without a Plan’ calls for a halt on the ban until guaranteed jobs are secured for the approximate 150,000-200,000 workers currently employed in North Sea operations.

However, environmental groups are calling for harsher government action against offshore projects. A prime example of the debate can be seen with Rosebank, the UK’s largest undeveloped oil and gas field that’s set to start production in 2026. While oil companies claim it provide vital power (not to mention revenue), environmental groups Uplift and Greenpeace UK took the matter to court in November, saying the project never should have been approved.

“The costs of continuing to drill are now vast and the benefits far too few,” said Tessa Khan, executive director of Uplift. “Rosebank is a terrible deal for Britain. It’s mostly oil for export, which would do nothing to lower fuel costs or boost our energy security.”

Instead, Khan said the renewable energy industry could provide the job opportunities needed for a stable transition. “Even with new fields being approved, jobs supported by the industry have more than halved in the past decade. Workers need clean energy jobs that have a long-term future,” she added.

Regardless of the UK’s decision the North Sea is facing the issue of declining production – with Offshore Energies UK reporting last year that production was down 13%. As such, calls for the government to ramp up renewable power have taken on greater momentum.

The need for renewables

While current renewable targets are challenging, they’re not impossible, and there are a few avenues the government could take to make it a reality. Mark Williams, head of analysis at Energy UK, said the main challenge is in building a lot of new equipment in a relatively short period of time.

According to the UK’s National Energy System Operator, previously owned by National Grid, nearly 1,000km of onshore and over 4,500km of offshore wind networks need to be built by 2030, as well as more than three times the amount of solar capacity (rising from 15GW to 47GW).

While investment opportunities are there, Williams said government action is needed to turn them into tangible outcomes. “Recent advice has estimated the cost of establishing this infrastructure and network capacity will be £40bn per year to 2030,” Williams said.

“That’s a lot of capital to mobilise. As almost all this funding will be delivered by private companies, and the role that the government will play is setting up the mechanisms to allow that to happen.”

Other challenges to be addressed, according to Williams, are establishing the grid infrastructure to connect assets, as well as improving regulatory processes to get these elements approved faster.

While the transition requires some smart manoeuvring on the government’s part, once set up it has significant potential to provide not only the much-needed emission reductions, but also the job opportunities that some fear will be lost in the transition.

Accessing the right skills is going to be an increasing challenge with the need to build new equipment, but there are lots of opportunities in the energy transition for that sort of re-skilling.

Paul Everingham, CEO, Asia Natural Gas & Energy Association

Offshore wind provides particular potential, with the Offshore Wind Industry Council estimating over 31,000 people across the UK are currently employed in the sector – a figure set to rise to 97,000 by 2030.

“Accessing the right skills is going to be an increasing challenge with the need to build new equipment, but there are lots of opportunities in the energy transition for that sort of re-skilling,” said Williams.

“Ultimately, whatever policy the government pursues, the North Sea is a depleting basin,” he added. “Jobs are going to fall off whatever happens, and it is the duty of the government and other public bodies to support those workers in a way that we have manifestly failed to do for other transitions.

“Scaling back offshore at the same time that we’re ramping up renewable technologies provides a real opportunity, because there is a sector to move these people into it in a way that there just wasn't for something like coal,” he added.

While the path to net zero is not clear cut, the potential of the renewables industry to take over not only most power generation but also job creation is there. With the Labour government showing decisive action on net zero, many industry members seem optimistic as to the transition’s future – with the proviso that offshore workers are handed a just transition.

“What we’ve seen with this new government is faster decision making, which is crucial to provide the stability to attract these much-needed investors,” said Baker. “If we can keep seeing this, creating a clearer vision for investors, it will be good news for the industry.”